While the real-time adrenalin and excitement of ISKME’s Big Ideas Fest 2015 have subsided, I wanted to share some personal take-aways about how to inspire collaboration to activate change in education.

First, is that listening to feedback and being open to surprises can result in new learnings for everyones. Big Ideas Fest 2015 was ISKME’s seventh engagement with educators with the purpose of fostering collaborative, problem-solving and transformation in education through action-oriented design sessions and thoughtfully curated, rapid fire speaking panels.

The format of Big Ideas Fest has changed over the years to give participants the best possible experience in learning from education change-makers about their innovation journeys, and helping BIFniks develop a mindset and practical approach to become an active change-maker in their own areas of influence. We pay a lot of attention to participant feedback (yes, we really do read those BIFnik surveys!) and continue to iterate on the format and process so that participants feel supported and are able to take risks, leave their comfort zone, and feel okay about not knowing where their efforts may lead them.

Big Ideas Fest is intended to be a collaborative experience, with speakers and guests participating in Action Collab design sessions and participants taking ownership of their group work. And sometimes they take over the agenda, like our student BIFniks did this year in the closing session when they wanted to share their culture with the rest of the participants. They intercepted the A/V team at the Dolce Hayes Mansion and proceeded to immerse and teach us their music and dances, for a final impromptu extravaganza that had everyone up on their feet with huge smiles on their faces!

Second, we need to embrace the power of story to re-focus and re-energize a group. This showed up several times at Big Ideas Fest 2015 and in different ways. Each time it brought us to new depths of understanding and insight, preparing us to imagine and explore more. Our opening panel of storytellers kicked off our first design challenge: How might we create educational opportunities to disrupt the school to prison pipeline? Tyson Amir-Mustafa from Five Keys Charter School (who teaches at the San Francisco County Jail) spoke about his work with young men and women in prison classrooms. Ashanti Branch, Founder of the Ever Forward Club, talked about his work with middle schoolers and their need for safe spaces to identify and share their emotions in order to develop greater emotional resilience. Both sharing their personal experiences of growing up as black men in America. Shanley Rhodes, Deputy Director of the Southern Region of Five Keys Charter, described her early years as a teacher in a violent and dysfunctional school and its personal impact on her as a teacher. BIFniks listened actively and openly to capture what they heard without interpreting or rushing to rationalize and solve.

The ballroom was thick with energy and emotion. We were all brought to a new place—a new perspective on a dimension of the education system that often is not the focus of “future of education” gatherings. Our expectation was not necessarily to solve this challenge in 6 hours, but to bring BIFniks to a new place in their thinking about this critical issue—to show them the complexity and tensions from authentic, personal voices, and to feel confident that there are practical solutions that can improve lives if we allow ourselves to see the challenge with new eyes.

As one BIFnik eloquently describes in her post, “listening deeply, I heard a common thread—a desire from the young people in these stories to be truly heard, known, and understood. It harkened back to the notion that it is really all about building authentic relationships and hearing someone for who they are and not who we assume them to be.” And in fact, several provocative solution ideas emerged from such insights: Mind the Gap is a board game that reveals the perspectives of different stakeholders to find common ground and connection on specific challenges; Invite to Insight is a set of invitation cards that students can use to invite a teacher to lunch for free and just talk; and BEASE is a program to overcome parent resistance to change at school by having parents “become a student” and “become a teacher” to learn the benefits of change in the classroom.

Kicking off Big Ideas Fest 2015 Action Collab work with powerful storytelling gave BIFniks permission to tell their own stories, and most of all, to create a space to listen deeply and openly to each other.

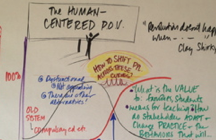

This is precisely why we use storytelling, among other techniques, as a part of ISKME’s Action Collab process. ISKME developed Action Collabs as a collaborative platform for educators problem solve creatively as peers and gain the insights and perspectives from each other’s distinctive perspectives and imaginations. By equipping teachers, principals, administrators, students, parents, and other education decision-makers with such skills, tangible change in education may become human-centered and emerge from the bottom up.

Finally, dessert helps! That BIFniks sampled a delectable assortment of cheesecakes, chocolate mousse, passion fruit cake and other sweet treats made no small contribution to the positive and open climate throughout Big Ideas Fest.

ISKME will be holding Action Collab trainings in March (28-29) and August (1-2) so that educators can develop and practice their collaborative problem solving skills and catalyze transformation in their own organizations. For more information on Action Collab trainings click here.

Originally posted on January 26, 2016 at http://www.iskme.org/our-ideas/cake-stories-and-imagination