Like many people, I’ve taken up a few new activities while sheltering in place due to Covid-19. Some more admirable than others: late night Netflix binging; sourdough bread baking; optional grooming, cocktails at 5pm-ish (ok 4pm); daily walks with my daughter; and pilates.

The last two I hope to continue after we’ve moved through the shelter-in-place stage of the pandemic and have a bit more range in our wanderings and interactions. The walks with my fifteen year old have been transformative for me. They’ve been a time to reflect together on how we are as a family and as a society. They’ve given me a window into the person she is becoming—her values and sense of purpose and agency.

The pilates started as something to do with my daughter, but now I do on my own. At first I groaned through it, barely lifting my leg off the mat as I struggled to balance and “bring my navel to my spine,” something I’d never considered before. But I continued. I enjoyed the time with my daughter and noticed that I was getting better. My core muscles became stronger. I gained flexibility and more control over my movements. I became more confident.

Flexibility. Strength. Confidence.

These are the attributes that organizations, and schools, need to face the uncertainty of our VUCA world: volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. This pandemic will not be the last shock to our societal systems and structures. Rather than freeze in the headlights of disruption, we can practice imagining the future in order to develop the strength and agility to approach the long term horizon with confidence. As with pilates, we can strengthen organizational resilience by exercising our strategic foresight muscles and practicing possible futures and their implications for schools, teachers, learners and families. We can exercise our ability to map uncertainty, explore provocations and imagine strategies.

What if schools and educational organizations practiced strategic foresight regularly, like pilates?

Could they reduce the anxiety and discomfort of facing an unknown and uncertain future and build the courage to innovate and create more life affirming systems of education?

This was the topic of discussion in a webinar I participated in, hosted by Chelle Wabrek, Assistant Head of School for Academic Affairs at The Lovett School in Atlanta, Georgia. Chelle is hosting a series, The Curiosity File, to cultivate the creativity and generative thinking among her staff, and educators who tune in, while they practice social distance and plan for the coming Fall. You can listen to the podcast here, and to others from this link.

Conversation Highlights:

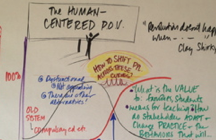

- Strategic foresight helps to regulate anxiety about innovation and the future by shifting educators away from their fight or flight responses to challenges and toward creative generation of provocations and possibilities. By mapping uncertainty and naming threats and opportunities, educators can move beyond fears and assumptions of constancy and uncover opportunities for meaningful change.

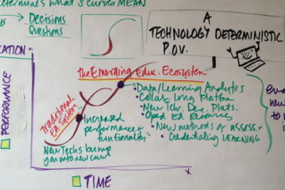

- The proliferation of smart machines—automation and artificial intelligence—is one of several significant system disrupters. It doesn’t, however, have to lead to a robot apocalypse. To counter the “robots as overlords” narrative, another one describes smart machines as organizational power tools that will support us in building flexible, human-centered organizations and experiences.

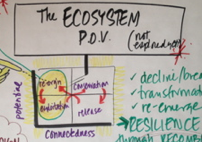

- Imagining schools as ecosystems offers a framework to generate creative responses to the VUCA world while staying aligned to values and purpose. As we’ve seen recently, teaching and learning is looking a lot different post-Covid19 than it did pre-Covid19. Visions of success will look different in the future, perhaps in unexpected ways. Ecosystems pose the question: are you a school, or do you have a school? What is your teaching and learning ecosystem and what role do you play in it?