This article is Part Three of a four-part series, Reframing Education for the Long Now, based on insights from the Long Now Educators Workshop on August 1, 02017, hosted by the Long Now Foundation and KnowledgeWorks Foundation.

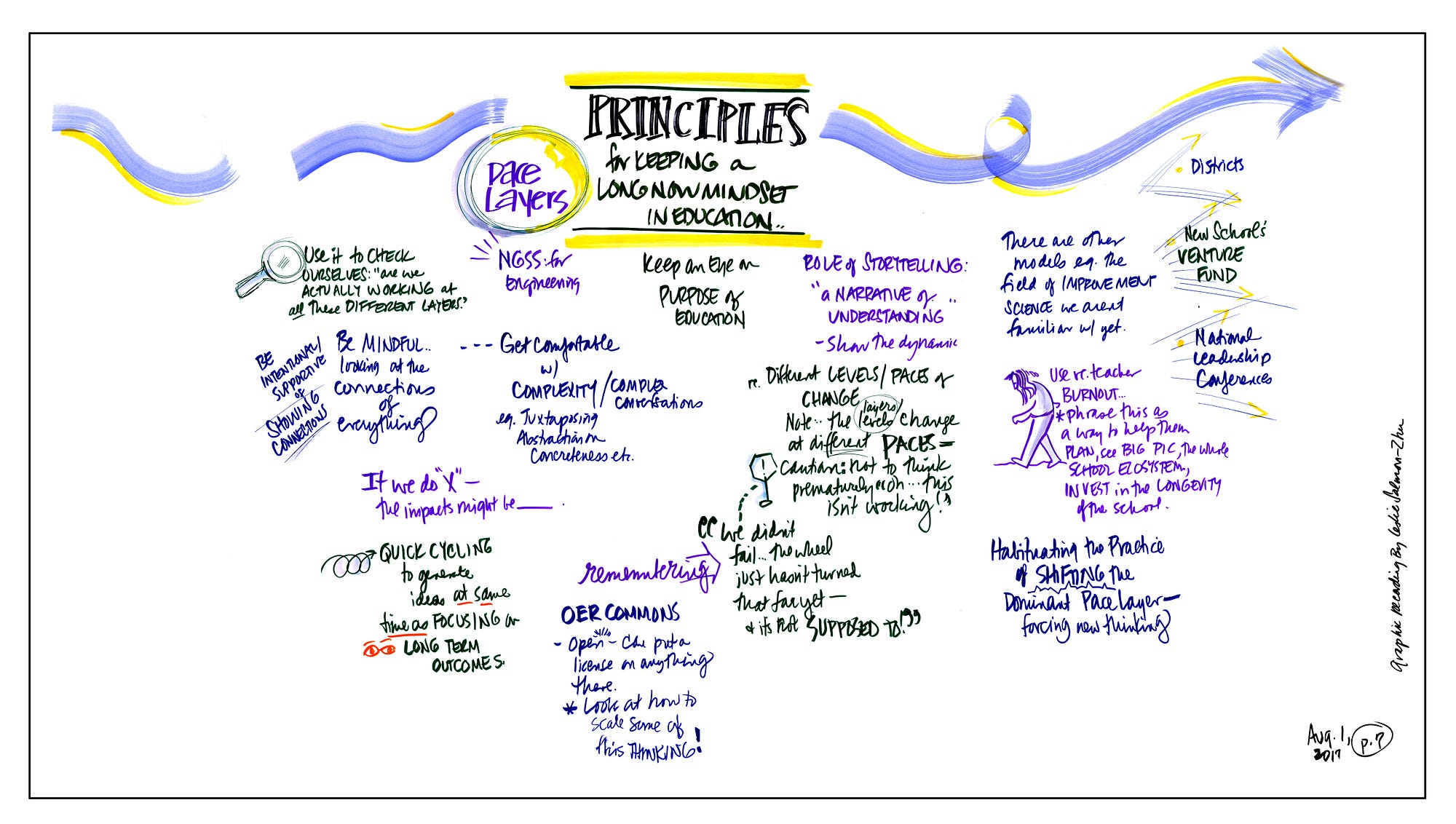

Long Now Educators Workshop, August 01, 02017.

As explored earlier in this series, the pace layer framework honors the messiness of society and provides a tool for revealing apparent contradictions across societal domains in ways that create opportunities to shift systemic interactions toward long-term health. As a tool for understanding such complexity, the pace layers offer a useful lens for identifying strategies for system change in education.

“The total effect of the pace layers is that they provide a many-leveled corrective, stabilizing the negative feedback throughout the system. It is precisely in the apparent contradictions of pace that civilization finds its surest health.”

— Stewart Brand, Long Now Foundation Founder

The various layers and their distinct paces of change reveal interests and interconnected relationships that emerge when different domains of civilization interact. Each pace layer offers a distinct perspective for developing strategies and interventions with the potential to trigger actions and responses across stakeholder groups. Brand suggests that, if we want long-term change, we need to engage the slow layers and pay attention to dynamics when layers intersect.

As we find ourselves with a very dominant commerce layer shaping the direction of change in education, how might the pace layers provide inspiration for creating an education system that is a robust intellectual infrastructure for our society?

A pace layer perspective offers a way to frame questions that help us focus on interactions across stakeholders and over time. For example, in education, we can ask:

- How we might we leverage the distinct pace and job of each pace layer to contribute strategies for bringing positive transformation to education?

- How might interventions at one layer engage the other layers in contributing toward positive system change in education?

- Are there actions we could take that would lengthen the “now” in education and help us think in terms of generations and centuries, instead of months and years?

These general pace layer questions serve as a guide for more specific questions that help explore and uncover new stakeholder actions and relationships to drive systemic change.

What if teachers were supported as disruptors to drive the creative churn of new ideas and innovations in education?

What could it look like if teachers led and drove creative, disruptive education research and design? Online collaborative platforms such as The Teachers Guild provides one form of support for teachers as designers of collaborative solutions to education challenges. How might we harness the fashion-art layer to make educator-centered innovation the driver of education research? What strategies might leverage the attention-grabbing possibilities of this layer to grow the public image of teachers as designers and innovators of learning experiences?

The recent XQ Superschool red carpet launch of their reimagine high school initiative on primetime television is one example. Building upon that, what might an award show for educators look like? What are other ways that schools of education, districts, and communities might partner at the fashion-art layer to support and recognize teachers as drivers of innovation and design? How might such a partnership need to be supported at the infrastructure and governance layers to be sustainable?

What if educational technologies and resources were predominantly open source, with its development and testing done via collaborative, peer-production communities for feedback and improvement?

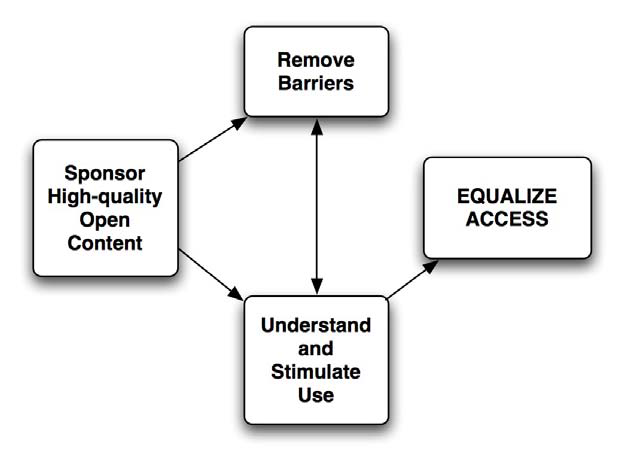

Commerce is about exchange among people to create value — it helps sort and filter the abundance from the fashion-art layer. What kinds of collaborative platforms could expand development and testing to broaden access to new educational technologies, ideas, and resources among educators? Open educational resource platforms, like OER Commons with its OpenAuthor tool, lets teachers develop and share curriculum, assessments, and other instructional materials. This type of platform and community of teacher “peer developers” could expand to become a platform for testing, feedback and iteration of new open source tools and applications.

Crowdsourced, collaborative design communities, like Open IDEO share data and ideas to generate feedback on innovations and on solutions to design challenges. How might these approaches expand to develop a more open source, peer development approach for innovating new school models, assessments, and education policy? How might new platforms for exchange bring education stakeholders together to revitalize education research and development and innovation to support a culture of change? What would it take to shift education to a culture of openness?

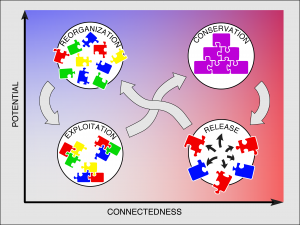

How might a responsive education infrastructure support dynamic teaching and learning ecosystems?

Infrastructure is intimately linked to governance and culture as these slower layers must justify the longer slower investment required to sustain infrastructures. What might education look like if it were modeled after the nature layer? How might ecological concepts such as resilience and adaptive cycles reframe our thinking about equity and shift our time frame to make metrics less punitive? How might the government pace layer support education in becoming more unbundled and more integrated within geographic communities? What might stewardship of a learning ecosystem look like? How might a diverse range of stakeholders manage a portfolio of public and private, in-school and out-of-school learning options that shared a common vision? How might a learning ecosystem respond and adapt to change?

How might we reinvigorate the conversation about the purpose of public education?

As explored earlier, commerce currently controls much of the narrative about the purpose of education. Driven by the uncertainty of future work, the purpose of education has shifted over the decades from its fundamental role of preserving and facilitating democracy to fueling the employment sector. As a result, the benefits of learning accrue to the individual and not necessarily to society. How might education change if we uncoupled notions of success from labor force participation? We’ve already seen GDP grow without an expansion of labor due to widespread application of digital automation and augmentation and other labor-saving or labor-replacing technologies in workplaces. What purpose might be served by education if the economy were to become much more automated? How might we “lengthen the now,” as Stewart Brand puts it, in our thinking about education to cultivate systemic goals and approaches that link individual gain to collective health? Looking even further down the pace layers, how might we link education to nature to create aspirations for education that serve both humanity and the planet?

Taking a pace layer perspective to examine and strategize about long-term transformation in education offers multiple ways to frame intention, outcomes, and metrics. In a sense, taking a pace layer perspective helps relieve the pressure on education decision-makers to solve everything immediately. Some interventions, such as a shift in pedagogy, learning space, or assessment strategy may take years, while changes to education structures, leadership and governance models and learning cultures may take decades.

Using the pace layers allows us to slow down and take the long view. Hopefully, this lengthening of perspective may calm some of the anxiety around education reform and transformation, help stakeholders operating at different layers empathize with one another and lead to sustainable solutions that support the ultimate success and wellbeing of all students.

The next, and final, blog post will reflect on the potential benefits of the pace layers as a tool for cultivating a long now mindset for education.