As I participate in discussions about the future of education, I listen for how the conversations get framed. Underlying most discussions about innovation and transformation in education are assumptions that tend to set the boundaries of discussions. Sometimes these frames are overt, sometimes hidden, but in any case they influence the kinds of questions that get asked and shape the solution space. They highlight some players over others and may orient towards particular solutions. Ultimately they shape how we view opportunity and visions of what is possible.

Here are three frames that I have noticed. I’m sure there are others out there too. When I sense that we are moving into one of these frames, I draw it out so that we can be explicit, work the frame to deepen our conversation, then move to another frame.

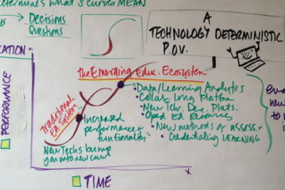

The performance frame is typically technology driven. It frames discussions by focusing on innovations that drive what teaching and learning could look like. (Time on the x-axis and performance on the y-axis.) These conversations tend to focus on what is possible from innovative ideas and new technologies. Questions focus on how emerging technology clusters and new conceptual paradigms enable improved system functionality and value. The key here is how performance is measured. It could be increased access (as with MOOCs) or greater affordability and relevance (as with competency-based education programs). Over time, as incremental gains decline and are exhausted a new set of technologies comes along and boosts performance to a new level. The benefit of this frame is that it can serve as a springboard for imagining new constellations of innovations that collectively could increase the performance of the system. It also focuses on highlighting definitions, measures, and values for system performance.

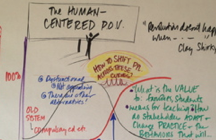

The adoption frame originates from Everett Rogers’ early work on the diffusion of innovation and recently is described as the “two curve” challenge, in Ian Morrison’s book, The Second Curve. (Time is on the x-axis and penetration rate is on the y-axis.) This frame is more human, and organization centered. It focuses on the threats and opportunities of innovations to specific users and stakeholders. It helps orient conversations around what might enable or inhibit adoption of innovations. For example, who doesn’t want to move to the new curve and what economic or political drivers may be the reason? Are there other barriers in the market or within an organization? This frame also is a good way to discuss what kinds of risks emerge, and when, from remaining on the existing curve too long or leaving it too early.

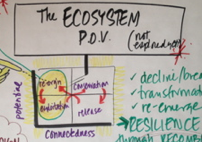

The concept of the adaptive cycle is at the root of the ecosystem frame. This lens on change in education helps us look at the breakdown and disruption of the traditional education system as part of an adaptive process to a newer system that is better aligned to its context and conditions. After a mature forest experiences breakdown and loss from fire, it re-generates itself by opening itself to unknown possibilities from potentially new species and relationships among plants, insects, wildlife, and nutrient flows. Productive relationships thrive and over time the ecosystem rebuilds itself in response to its new conditions.

The ecosystem frame is particularly useful for orienting education system discussions around new opportunities, potential value, and relationships. The frame highlights the generative dynamic of relationships and novel responses to threats and disruptions. Rather than resist disruptions (such as new technologies and innovative organizational models) or fall back on existing (ineffective) responses, the ecosystem frame points out adaptive responses by examining opportunities created by the release of resources, re-organization of relationships, and exploitation (leverage) of new niches in the ecosystem.

We’re currently in the early period of exploitation in which novel combinations of players are testing the ground and seeing what kind of sustainable value they can create. Content and curriculum development is proliferating among open educational resource spaces that support new combinations of teachers, experts, and learning agents like librarians. New ideas like blended learning and competency-based assessment are attracting experimentation and pilots. The most damaging action to the education ecosystem now would be to stifle experimentation (the exploitation of opportunities presented by new ideas, technologies, and players) and the learning obtained from successful and failed initiatives.

The adaptive cycle is nature’s learning process that supports its resilience over time. For this reason, the ecosystem frame is a useful one for challenging the rhetoric around experimentation and failure (as in “don’t experiment with my children”) and creating a more productive conversation focused on learning and system improvement.

See my earlier post for a detailed explanation of the adaptive cycle.