Reflections on Cultivating a Long Now Mindset in Education

Insights about how Pace Layers contribute to a long now mindset in education

This article is Part Four of a four-part series, Reframing Education for the Long Now, based on insights from the Long Now Educators Workshop on August 1, 02017, hosted by the Long Now Foundation and KnowledgeWorks Foundation.

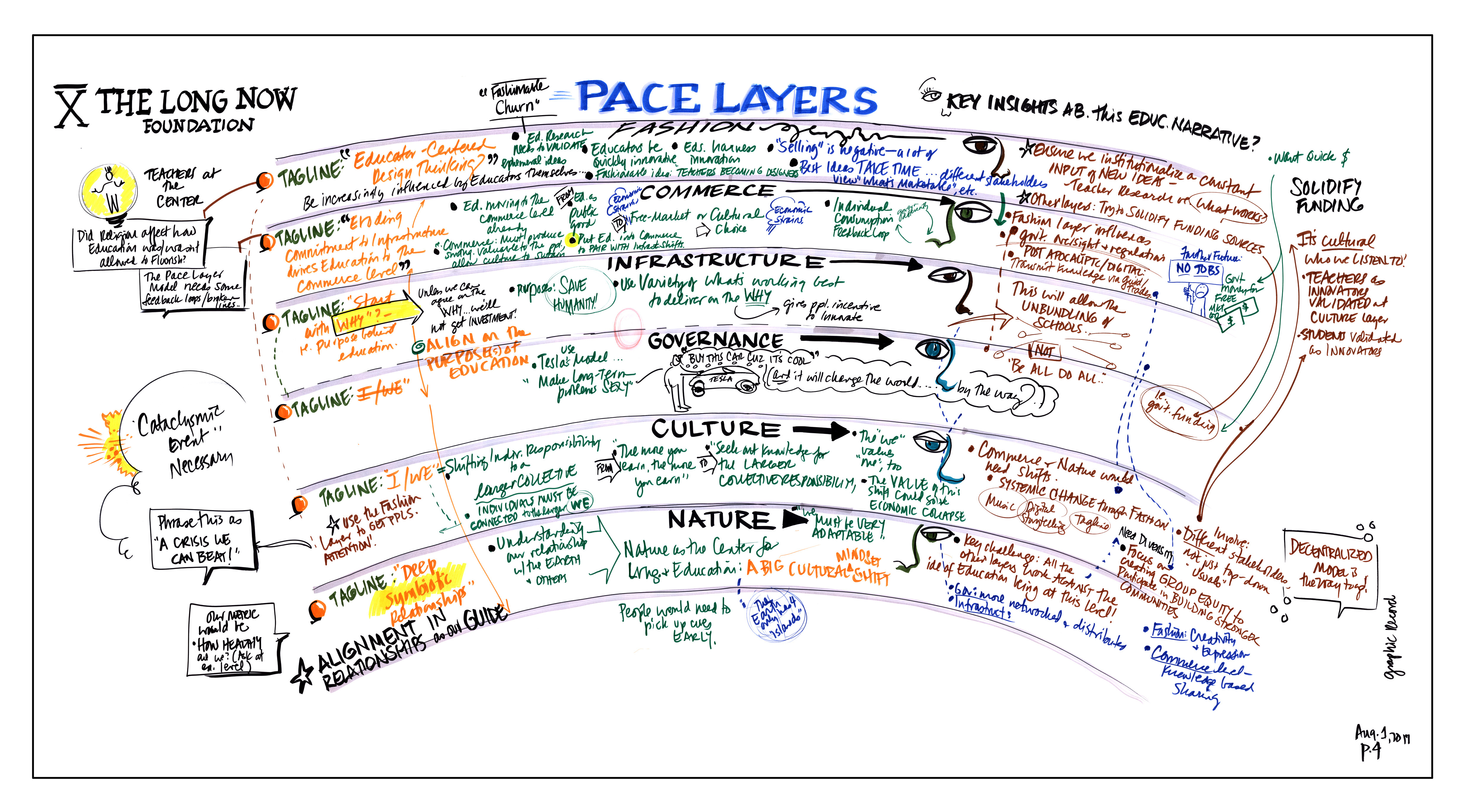

This series explored how as a society we might develop a long now mindset to examine and reframe education challenges. The culminating discussion of the Long Now Educator Workshop provided a time for participants to reflect on their insights about the benefits of using the pace layers and long-term thinking in education.

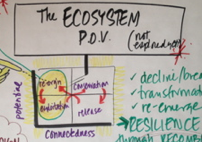

One theme throughout the conversation is the uncertainty about the purpose of a compulsory public education system. Public education lives in the slow layers of governance and culture, resulting in fragmentation of approaches and interventions. Promoting diversification of education reform strategies can be useful for system-wide learning as well as for identifying effective innovations. However, the lack of shared cultural guideposts to steer change is causing resistance, politics, and other obstacles to consume attention and prevent real transformation. It is also enabling the commerce layer to have undue influence over education reform. (as described earlier).

Jason Swanson, KnowledgeWorks Foundation

At first, this dynamic may seem deeply troubling. But the pace layer framework places this complex interaction in a longer timeframe. What might appear in the short view to be ossification of the public education system is in the long view really just temporary stasis. The current dynamic of education reform will shift when new pathways to change are built and are connected across the pace layers. The long now mindset cultivates the connection of the long term with the present moment to guide change. As mentioned in earlier posts, aligning expectations for change to the distinct pace of each layer might encourage more patience when change doesn’t happen quickly in the short term. It also helps to focus actions on achieving long term goals. As Stewart Brand suggests, we need to appreciate and engage the “many-leveled corrective” capability of the pace layers to stabilize negative feedback in the system.

Megan Simmons, Institute for the Study of Knowledge Management

Benefits of Pace Layer Thinking

The workshop participants reflected about the ways that the pace layers might contribute to their thinking about systemic transformation in education. They identified several specific benefits:

Supports systemic narratives. The pace layers encourage big storytelling across many layers and time periods that has the potential to reveal deeply embedded cultural values and their manifestation across societal dynamics. This creates the potential to shift cultural values that may no longer serve broader educational goals for society.

Encourages perspective taking across the system. A pace layer lens exposes motivations and intentions of diverse stakeholders and their deep histories. This opens up the possibility to build empathy for stakeholders and hope for the future. It also sets up education leaders, designers, decision-makers, policy-makers, and philanthropists to look for connections and opportunities to coordinate strategies for maximum impact.

Frames complexity. Big systemic narratives can help illustrate multiple cause and effect relationships of actions across the pace layers and how they connect to stakeholder intentions. Pace layer-driven narratives and analysis helps make complexity concrete. They help education decision-makers hold a complex picture of change in their minds and make sense of the apparent messiness of the system.

Clarifies expectations of outcomes. A pace layer framework for analysis can help set reasonable expectations about the scope and time frame for outcomes. Pace layers can become a shared language to form questions and discuss projects, outcomes, and partnerships. Example questions include: What layer is the focus of your program/project? What outcome can we reasonably expect from this layer? What if we focused on a different layer?

Re-contextualizes failure. Building on outcome clarification, pace layers have the potential to reframe failure and provide a richer language to discuss negative outcomes. What might have been considered a failure may just be a focus on the wrong pace layer or metric.

Diversifies innovation and problem-solving. The pace layers provide six domains of activity to explore solutions and interventions for transforming education. This allows for additional perspectives and prompts for brainstorming and prototyping new ideas.

Mark Kushner, education strategist and innovator

Now Lengtheners

To wrap up the workshop, participants playfully brainstormed and prototyped actions that might lengthen the now in education. Specifically, they considered the kinds of aspirational images, projects, or activities would shift the mindset in education to a longer term societal context.

Some compelling examples include:

The long view of human learning. What if we showed human learning in the context of the learning of the species? How would this expansive time frame influence system priorities outcomes?

Big data perspectives. What if we used big data to develop scale models and maps that let individuals put their experience into this bigger, longer perspective?

Learning legacies. What if we based our designs of education keeping mind the education needs and aspirations of our grandchildren’s children? What could be our individual and societal learning legacies to future generations?

Global/generational challenges. What if we trained students to solve intergenerational problems with intergenerational solutions? Many of our most complex challenges require strategies that endure centuries. Some examples include: interstellar space travel which requires generations to complete a mission; preserving the redwoods which requires an institution and people who understand the problem to span generations.

Values shift immersive game. What if we could immerse people in future scenarios that are guided by different societal values to show long term impacts? The experience might help reveal long term benefits and consequences to education of specific decisions, actions, and inaction.

Conclusion

Nasif Iskander, San Francisco University High School

Fundamentally, the pace layer framework is a thinking tool of hope and possibility. By expanding perspective to the breadth of civilization and timeframe to include centuries, pathways for positive change become more abundant and visible. One participant summed it up well.

“Each of these layers, while they have their own pace, each have their own values and motivations. And in all our conversations about school we tend to focus on what effectively is one layer and one set of values, and wish the others didn’t exist. The realization that all of this is at work all the time, and all this is necessary, and that this is a part of a functional system of the evolution of civilization is actually quite liberating. And I start to think of these different paces and different motives and values as opportunities rather than obstacles.” — Nasif Iskander