Andrea Saveri, Saveri Consulting.

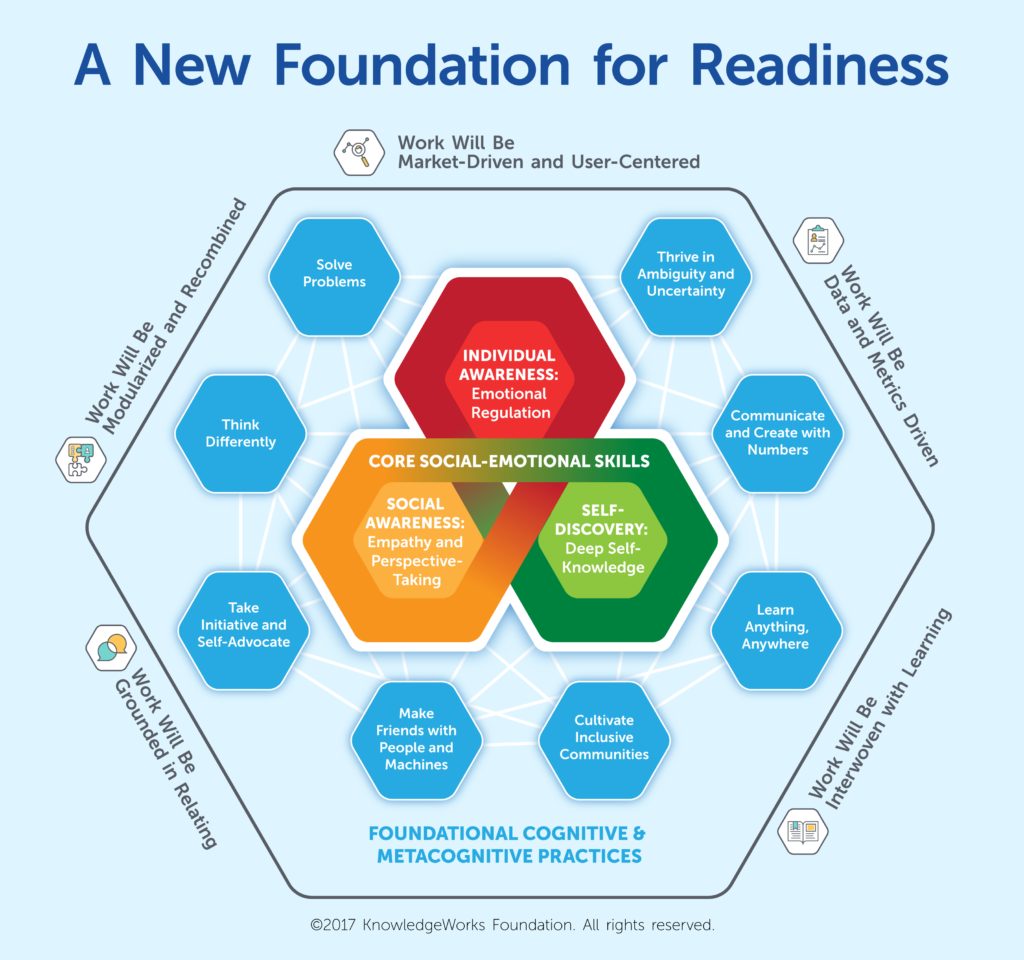

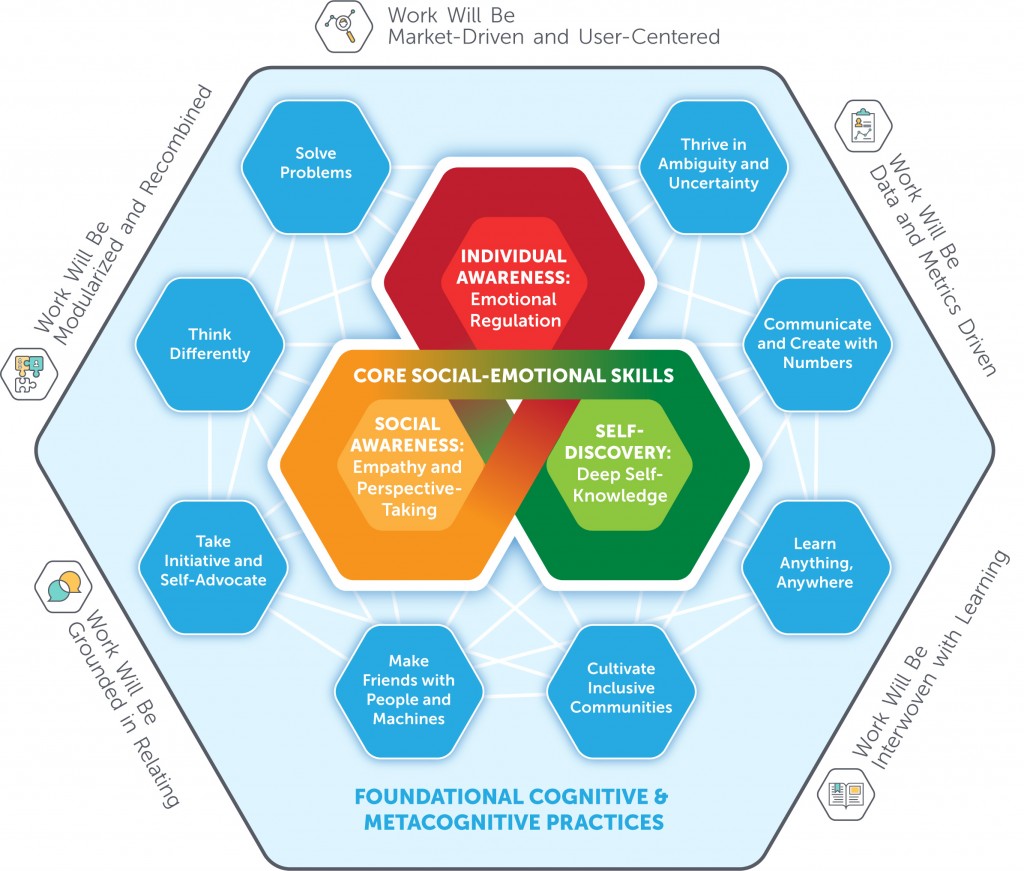

The distinctive human advantage in careers and life is shifting beyond cognitive skills to include relational, creative, and emotional competencies. Complex thinking will remain critical, but it will not be a sufficient foundation for individual success as computing power grows exponentially and as workplaces become more diverse and engage in complex problems that require inclusive and collective talents.

Successful organizations, from corporations to community-based movements, are recognizing the growing importance of unlocking individuals’ creative, relational, and emotional powers. We’re seeing an emergence of a new kind of smart, resulting in the need for a new kind of readiness and educational experience—one that prioritizes individual emotional and cognitive development with extreme social awareness and cultural navigation skills. In order to develop the necessary practices to thrive in the future, schools will need to invest in building their students social-emotional core.

Future Readiness Relies on a Social-Emotional Core

Source: KnowledgeWorks Foundation, 2016

A Rapidly Transforming Workplace

Business professor Ed Hess writes,“The new smart will be determined not by what or how you know but by the quality of your thinking, listening, relating, collaborating, and learning.” (1) Columbia Business School professor Katherine Phillips further explains the criticality of these relational skills for navigating complex diversity in order to leverage its robustness and drive organizational creativity and innovation.(2) People who differ by race, gender and other factors bring unique information and experiences to the task at hand. As diversity and inclusion shape a more equitable organizational culture, groups begin to anticipate the need to navigate perspectives and provide deeper rationales, thereby engaging in richer cognition and achieving better outcomes.(3) With collaborative work growing as an essential feature of the future workplace (expanding 50% in the past 20 years) (4), learning how to cultivate inclusive, productive communities will be a highly valued skill. For schools, Gurin argues that a diverse student body is as critical a learning resource as quality facilities, faculty and libraries.(5)

Many organizations are already aligning their training, hiring, and work practices toward relational competencies to adapt to global markets and drive outcomes.

- FedEx’s “People First Leadership” program teaches managers how to develop their emotional intelligence to make better decisions and create a culture in which everyone feels the dedication to strive for exceptional performance. (6)

- Google’s “Search Inside Yourself” course trains its engineers in emotional intelligence skills to support collaboration, more open communication, transparency, and less posturing.(7)

- A LinkedIn survey of business recruiting and hiring managers, 78% identified diversity as the biggest game-changing trend for business; more than half of these are focusing on implementing “diversity-inclusion-belonging” strategies to foster wellbeing and high performance.(8)

Educators Driving Change for the Future

The powerful partnership of relational competence and machine intelligence that augments our human sense making will transform society and bring us to a new threshold of creativity and fulfillment. In order for everyone to get there, educators must prioritize social-emotional intelligence and cultural competence as the building bocks of student growth. Many schools are beginning to take up the challenge and prioritize emotion-based and relational competencies in their school designs.

A recent OECD study examining skills necessary for social progress and wellbeing found that SEL positively contributed to students’ academic, career and life outcomes.(9) In fact, they reported that low levels of social-emotional skills can prevent the use of cognitive skills, becoming an obstacle for students to reach their educational and life goals. Schools nationally are seeing positive results in academic achievement, classroom climate and pro-social behaviors when they implement the RULER approach, an evidence-based social-emotional skills training from Yale’s Center for Emotional Intelligence.(10) Pioneering independent schools such as Prospect Sierra School,(11) the Keys School(12) and the Park School(13) are integrating SEL, cultural proficiency and pedagogy, and social justice strategies to create multifaceted approaches for fostering equity across the learning experience at their schools.

Relational Readiness for the Post-Industrial Age

Together, these strategies will help graduates build new kinds of adaptive careers necessary for the future, post-industrial age that are fueled by creativity and innovation and require emotional, relational, and collaborative competencies.

| Industrial Age Careers | Post-Industrial Age Careers |

| Human as asset of production. | Human as instigator and creator of novel work. |

| Work tasks are discrete and specified, requiring specialized knowledge. | Work tasks are complex, ambiguous, and problem-based, requiring diverse talents. |

| Organizational structure dictates functional roles. | Rapidly changing market forces shape roles and makeup of collaborative teams. |

| Careers are linear; sequential pathways are determined by employers, professional silos, and industry needs. | Careers are personal, creative journeys emerging from purpose driven challenges, professional and lived experiences, and interaction with diverse social networks. |

| Individual skill building is periodic, and externally determined by the market. | Ongoing self-discovery drives continuous learning, relationship building, and re-assessment of purpose. |

Source: Saveri Consulting, 2019.

The author would like to thank Rebecca Hong, Director of Institutional Diversity, The Spence School and Adrienne Barr, Executive Director, New York Interschool and Faculty Diversity Search for their review and input.

Sources

1 https://hbr.org/2017/06/in-the-ai-age-being-smart-will-mean-something-completely-different

2 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/?print=true

3 Patricia Gurin, The Educational Value of Diversity, in Defending Diversity, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, 2004.

4 https://hbr.org/2016/01/collaborative-overload

5 Patricia Gurin, The Educational Value of Diversity, in Defending Diversity, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, 2004.

7https://www.fastcompany.com/3044157/inside-googles-insanely-popular-emotional-intelligence-course

10 http://ei.yale.edu/evidence/