This article was previously posted on Medium. It is Part Two of a four-part series, Reframing Education for the Long Now, based on insights from the Long Now Educators Workshop on August 1, 02017, hosted by the Long Now Foundation and KnowledgeWorks Foundation.

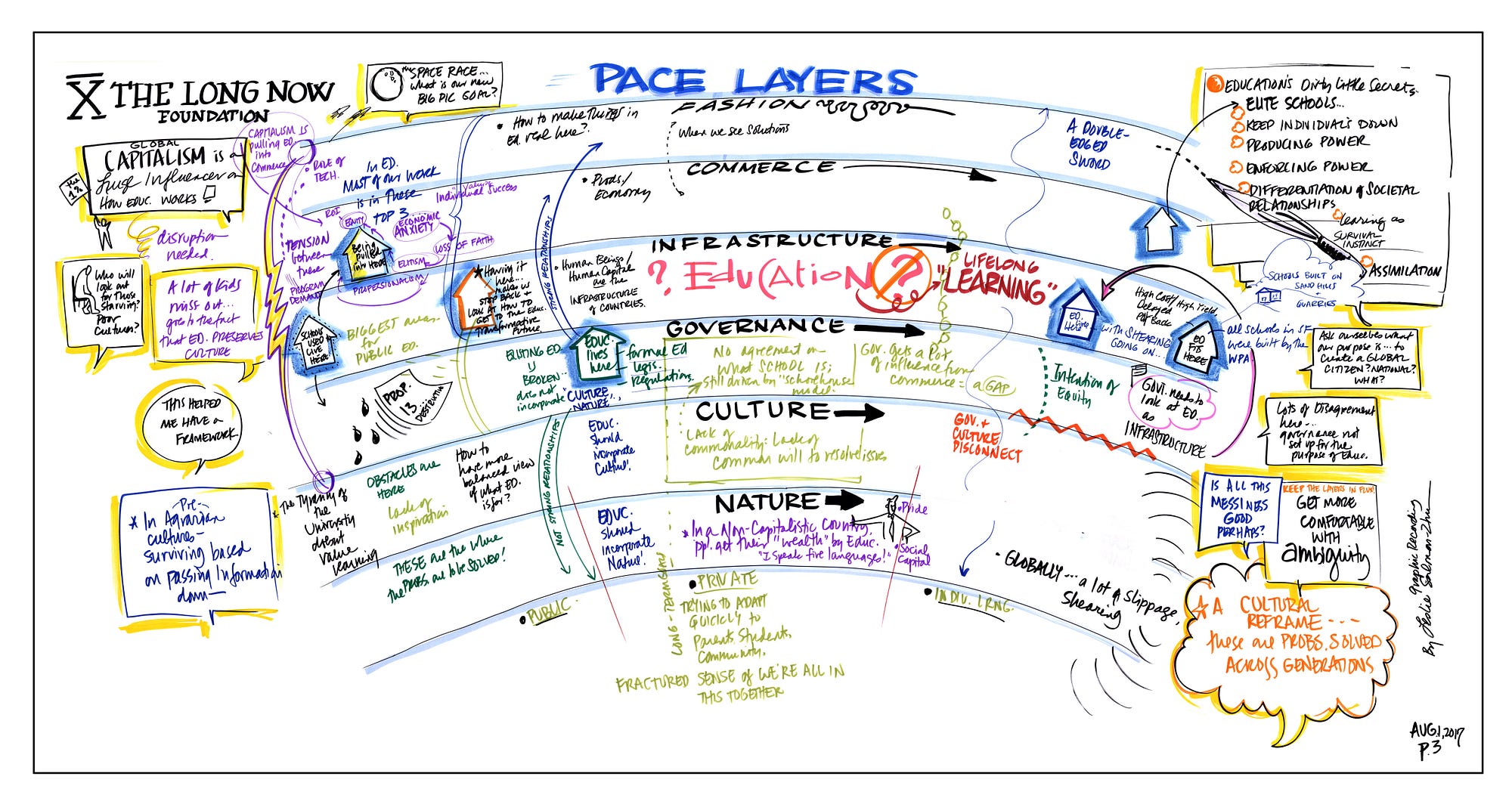

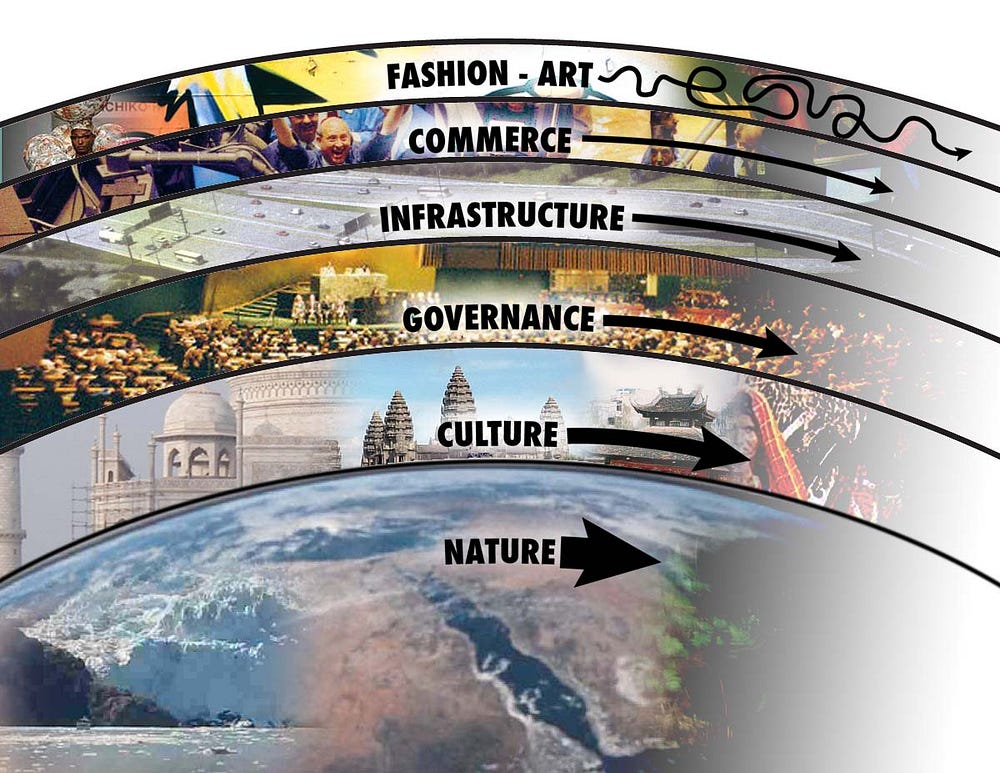

Looking at education through the lens of the pace layer framework provides several insights about the dynamic of education as intellectual infrastructure in the U.S., and where long-term transformation might emerge. In The Clock of the Long Now (01999), Stewart Brand describes education as intellectual infrastructure, situating it in the middle of the pace layers.

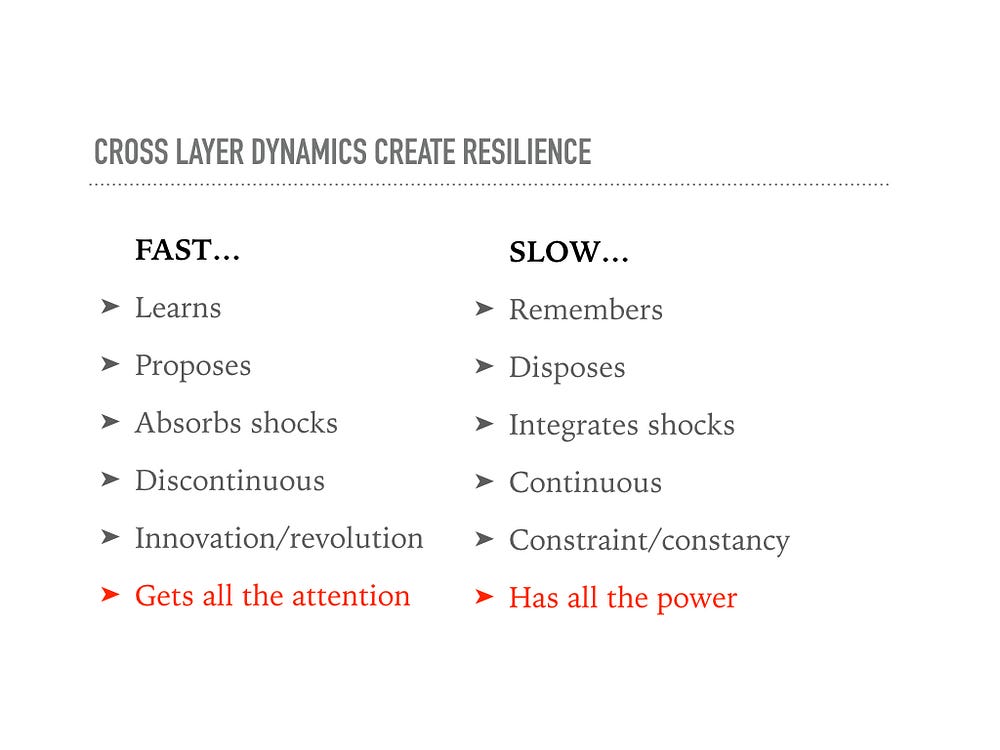

There it is bracketed by the turbulent, questioning, and disruptive forces of fashion and commerce on one side, and by the stabilizing constraints and forces of constancy and preservation from governance, culture, and nature on the other. In this middle pace layer position, infrastructure is capable of moderately-paced change — which should be measured in decades. As a form of intellectual infrastructure, education is well-positioned to take advantage of both the rapid testing of new ideas and approaches from the fast layers and the ability of the slower layers to purposefully integrate selected, meaningful disruptions.

As intellectual infrastructure, education represents society’s approach to developing its future generations with the purpose of ensuring its sustainability. It is society’s platform for developing its people — its human creativity and acumen—which in turn feeds the faster layers of fashion and commerce and supports the stability of slower layers of governance, culture, and nature.

The challenge of education as society’s intellectual infrastructure is to provide reliability and effectiveness to its constituents. That means being receptive to the propositions from fashion-art and commerce layers, even sometimes encouraging disruption and shock, while also seeking continuity and holding to society’s deeper values and principles. Any form of infrastructure requires large investment to do its job well, producing high but delayed payout over future decades. As Brand reminds us, societies need to be able to span these delays of payout and reward:

“Hasty societies that cannot span these delays will lose out over time to societies that can. On the other hand, cultures too hidebound to allow education to advance at an infrastructural pace also lose out.”

— Stewart Brand, The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility (01999).

This is the delicate dance of education as intellectual infrastructure: to cultivate societal patience in order to set innovation free and to use deep purpose to filter and integrate disruptive propositions in ways that make education more relevant to new societal circumstances.

The Effectiveness of the Slow Layers for Education Transformation in Finland

Finland seems to be striking this balance well, with culture and governance acting in partnership with educators to guide and evaluate innovation in schools at a steady pace. Its current adaptive innovation is intended to enable more fluid, integrated learning. That approach combines open-space layouts for learning environments with multi-age learning cohorts and the elimination of rigid disciplinary boundaries between subjects.

The approach is built on trusting educators and students. It allows teachers to drive curriculum, rather than follow a standard set curriculum. The benefit is the ability to effectively create ways to integrate competency development freely across subject matter and collaborate across grade levels to create higher-level thinking and multidisciplinary learning experiences. Students navigate physical spaces and social groupings to support their own learning. To effectively implement and achieve the benefits of this innovation, Finnish educators have broader society’s trust.

“The kind of freedom Finnish teachers enjoy comes from the underlying faith the culture puts in them from the start, and it’s the exact kind of faith American teachers lack.”

—Chris Weller, Business Insider

Operating at the infrastructure pace layer, Finnish teachers drive change in the education system with the support of the culture layer and enabling structures established by the governance layer. In the U.S., the culture layer has become fragmented with competing narratives about the value and purpose of education creating churn at the infrastructure layer that the governance layer struggles to help manage.

Pace Layer Tensions in U.S. Public Education

Change in public education in the U.S. is strongly shaped by the dynamics of the commerce layer, with market values, business rationales, and global economic imperatives shaping education decision-making. Commerce is rapidly introducing new educational technologies and pedagogical approaches at a pace that outstrips the capacity of other layers to engage effectively and exert their influence. This dominance of the commerce layer has been recasting education with language, values, and purpose that serve commerce stakeholders — business interests — but not society at large. The result has been a shift form treating education as the public service it should be to treating it as a market good.

Exacerbating this imbalance, accelerating technological change has created flux at each pace layer and has heightened uncertainty about the future.

Workshop discussion about the impact of an unchecked commerce layer on education included the following insights:

The market determines the value of education. Both hyperconnected global markets and increasing automation and digital augmentation are challenging established economic and business models, the structure of organizations, the notion of work, employment patterns, and even the nature of what it means to be human. The cultural narrative emerging from this context is that people are human capital — an asset whose value is determined by the market. Our societal definitions of success and how we determine student readiness to navigate society have become tightly tethered to the global market. Education critics have written about the link between the origins of compulsory education and the factory model school with the needs of early industrial society, so this link is not necessarily new. The challenge is whether the purpose of education continues to be narrowly evaluated in terms of serving the requirements of commerce rather than broader societal needs, such as the needs to support pluralistic society, democracy, and a sustainable planet.

“Solutionism” shortens the time frame and scope of reform. The education technology sector has grown rapidly, shaping the process, language and expectations of education reform. The ed tech rationale argues that the way to “fix” education is to configure the right suite of applications and devices without much concern or understanding for the root causes of education’s most pressing challenges such as achievement gaps, inequity, teacher support and professional development, and student engagement. The language and process common in Silicon Valley of “solutionism”—promising quick fixes, profitable return-on-investment, and scalability—has a stronger role in guiding decisions about education investment. Solutionism has permeated the education reform space in ways that has shifted mindsets and expectations about the timeframe and scope of change. Linking such activities to longer and slower processes of transformation in the governance and culture layers is lacking.

Mismatched metrics. The spillover effect of technological solutionism is that the expectation for change is measured in months and years rather than in decades. While it may be appropriate to measure reading and mathematics performance yearly (or more often), measuring social and behavioral practices and cultural shifts in meaningful ways takes longer and require metrics that span years and decades. Carol Dweck, the pioneer of the popular “growth vs fixed mindset” concept, has written articles and changed her book to warn against the “the false growth mindset” to counter simplified, shortcut, ineffective implementations of her concept. She reported that teachers were not able or willing to commit to the longer time frame to integrate fully and develop the growth mindset practice in their classrooms. The allure of quick solutions is that they make us think that there are immediate outcomes.

Implications for Long-Term Change

While the commerce layer seems to drive decision-making and innovation in education in inappropriate ways today, this pace layer does do well at absorbing disruptions and responding quickly to immediate needs. A challenge for education decision-makers today is to find ways to better harness commerce to provide a more equitable system and one whose purpose serves broader society. The venerable Peter Drucker reminds us about the link between the tension of short- and long-term interests:

“Building around mission and solutions is the only way to integrate shorter-term interest.” — Peter Drucker

Brand also warns that any meaningful long-term change will need to integrate the slow layers of culture and governance.

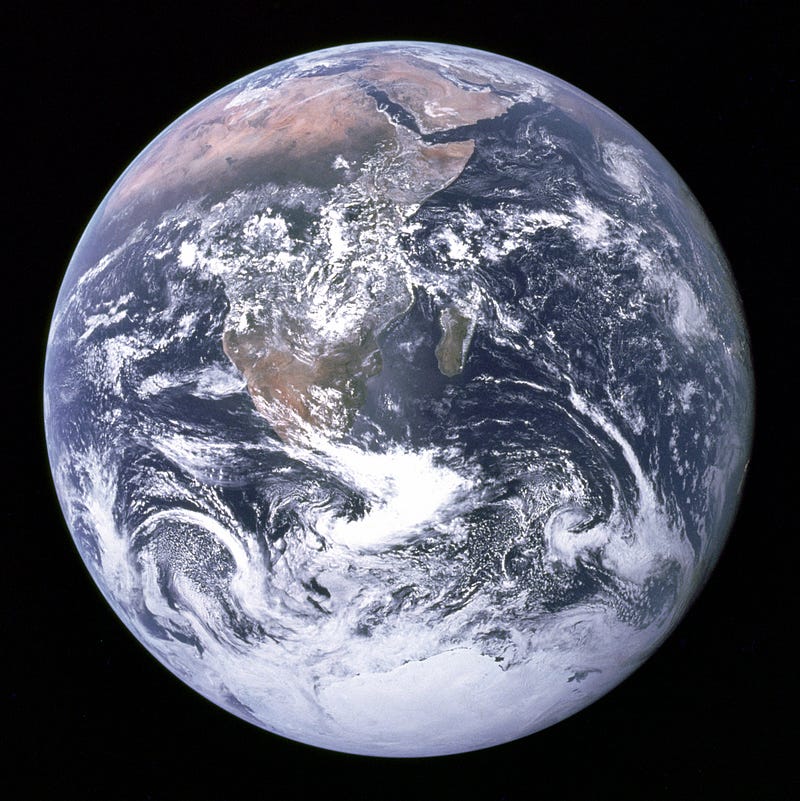

In the current education narrative, nature is largely left out as a significant influence. However, this layer may provide inspiration for reframing education and designing interventions across the pace layers to shape a new purpose for education that speaks to our collective humanity, global interconnectedness, and shared responsibility to steward our delicate relationship with nature.

The earth photo from the moon showed that national solutions were not sufficient to solve global ecological challenges. Education solutions may also need to transcend national borders, taking their cues from a globally interconnected and planetary context.

The next blog post in this series will explore the possibilities for leveraging pace layer strategies to create system change in education.